Three Legislative Options for Redeveloping Unused Hotel Space into Mixed Income Housing Units in New York City

Scott A. Schreiber

Since well before the Covid-19 crisis, indicators of the financial health of the hotel industry in New York City have pointed toward a downturn. Revenue per available room (“RevPAR”), a key metric used by the hotel industry in describing the economic health of the sector, had been declining in the New York area in the months and years leading up to the current crisis. Analysts had begun discussing the likelihood of an economic downturn well before Covid-19 upended our reality, partly owing to a surge in hotel room stock due to overbuilding. Over the past three months, these estimates have become conservative in their forecasting of an economic slump in the hotel industry, as a grimmer picture has begun to emerge. Now, with the complete shutdown of the industry and uncertainty regarding when, or even if, we will see a return to a sense of pre-Covid normalcy, hotel owners are struggling to hold on to their properties, and the possibility of turning a profit looks more and more like a bygone relic of a more certain time.

The surplus of available hotel space, coupled with the abrupt stem in flow of people to occupy that space, provides the perfect opportunity to rethink how that space is being used, and to develop the infrastructure for redeveloping that space in more efficient and beneficial ways. Historically, tax abatements and exemptions have provided added incentives to developers sufficient to convince them to focus development in ways deemed important by the legislature. With a few pen strokes by either the New York State Legislature acting alone, or in concert with the New York City Council, existing legislation could be modified to significantly overhaul existing tax abatement and exemption programs, leading to precisely the type of incentives developers would need to convert prime underutilized real estate into livable space for low- and middle-income New Yorkers, while putting more dollars in developers’ pockets. Using relevant existing legislation, both current and expired, this article analyzes three possibilities that could be enacted relatively quickly, and which would provide the impetus for developers to begin redevelopment.

J-51

J-51 provides a tax abatement and exemption to the conversion of a hotel into a Class A multiple dwelling, where at least 50% of the floor area of the completed building consists of pre-existing floor area.[1] In the legislation’s current form, such conversion would be eligible for J-51 benefits only under limited circumstances, including a requirement that construction be completed by June 30, 2020. Since eligibility for J-51 is based upon a project’s completion date, not the commencement date, an extension of at least three years is needed. Eligibility could instead be based upon the commencement of construction, rather than its completion, but an extension of the deadline of June 30, 2020 would be required in either situation.

Furthermore, J-51 benefits are limited to such conversions that are carried out with substantial governmental assistance (“SGA”). Such requirement could be modified to require that conversions include an affordable housing component. While the specifics of such a program may vary, i.e. the percentage of units and applicable AMI, the affordability options enumerated under the Affordable New York Housing Program provide a good blueprint. In addition, as the use of SGA has the added benefit of extending time to complete construction from 30 months to 60 months, such extension should also be made available to any project that contains affordable housing, as discussed above.

The legislation in its current form provides a further barrier in that it severely limits the tax exemption to which a project is eligible based upon the average assessed value per dwelling unit after completion of construction (“Average Assessed Value”). The current cap for projects south of 110th Street in Manhattan is an Average Assessed Value of $38,000 per unit, above which the project is not eligible for any exemption. Given the value of real estate in Manhattan, it is apparent how such a cap essentially prohibits any J-51 benefits in Manhattan south of 110th Street. With the goal of redeveloping hotel space in mind, a substantial increase or complete removal of the cap is required for this option to provide any significant benefit in Manhattan, the epicenter of underutilized hotel rooms.

421-g

Pursuing this route would require the legislature to modify and reauthorize Section 421-g of the New York State Real Property Tax Law (“RPTL”), as expanded by the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development rules (the “rules”). 421-g allowed eligible multiple dwellings to receive tax benefits in the form of partial exemptions and abatements in an attempt to increase living space in lower Manhattan, but only applied to building permits issued by the Department of Buildings from July 1, 1995 to June 30, 2006.[2] Thus, step one would be bringing the code up to date.

As written, 421-g limited benefits to the conversion of non-residential buildings into Class A Multiple Dwellings in Eligible Areas (“Eligible Multiple Dwelling). For our purposes, changing the statute to apply solely to “hotel or Class B Multiple Dwellings” would address the issue at hand, and requiring every project to include an affordable housing component would have the added benefit of increasing the number of affordable units in New York City. However, to accomplish that last goal, 421-g must also be changed to reflect a broadened target area. Owing to its roots in redeveloping Lower Manhattan, 421-g only affected a small portion of lower Manhattan. To be of any import in solving the Hotel/Housing Crisis, the statute must reflect a far more comprehensive area.

In its current form, 421-g grants a partial real estate tax exemption based on the amount of assessed value attributable exclusively to the physical improvement of the premises, and an abatement on the amount of real property tax that would have been due but for such abatement, after subtracting the exemption. Expansion of the basis of the exemption to include not only the assessed value attributable to physical improvement, but to include equalization increases as well, would help boost the case for a 421-g revival. Expanding the basis would protect applicants from unfair assessments in which assessors attribute increases in assessed value solely or predominately to equalization, resulting in minimization of the exemption ultimately granted.

Lastly, any of these proposed changes are worthless if they are not enough to entice developers to refocus their efforts. Under the Court of Appeals’ recent ruling in Kuzmich v. 50 Murray St. Acquisition LLC (34 N.Y. 3d. 84), dwelling units in rental buildings receiving Section 421-g benefits are not subject to the luxury deregulation provisions of the Rent Stabilization Law of 1969. Explicitly allowing for such luxury deregulation of residential rental apartments in the new and improved 421-g would go a long way in convincing developers that providing more affordable housing is ultimately in their best interest as well. Similar to provisions within Section 421-a(16) of the RPTL, owners should be permitted to remove apartments from rent stabilization where the rent for the unit exceeds the “high rent” decontrol limit.

421-a(16): Affordable New York Program

Procedurally, modifying Section 421-a of the RPTL and the corresponding Rules would be similar to modifying 421-g. By including a carve-out for Hotel Conversions, as that term would be defined in an updated statute, the current program could be easily applied to address the issue at hand.[3] For instance, the current language provides benefits to Eligible Conversions, as defined therein, which require that the resulting multiple dwelling retain no more than forty-nine percent of the pre-existing building or structure. In order for the program to benefit hotel conversions, the Hotel Conversions carve-out should include properties retaining more than forty-nine percent of the pre-existing building or structure. Furthermore, the updated statute should reflect an expansion of geographic area in which hotel conversions would be eligible for Affordable New York Program benefits by including projects in the borough of Manhattan located south of ninety-sixth street.

A further roadblock within the current legislation is the requirement that a resulting project include at least one affordable housing unit for every dwelling unit that existed prior to conversion. For the statute to be beneficial to hotel conversions, hotel rooms must be excluded from this replacement ratio requirement.

Lastly, the benefit for Affordable New York Program projects would provide only a nominal benefit to eligible conversions from hotel units. As discussed previously, any solution must provide enough incentive to developers to entice the desired behavior. Therefore, the inclusion of an additional 50% abatement on the amount of real property tax, as well as an elongated period of tax benefit eligibility would provide a reasonable benefit for such conversions, and one of which developers are more likely to make use.

Conclusion

It is no secret that a new world order has taken hold. Hotel capacity is at an all-time low, with many hotels completely shuttered for the time being. Even before the life-altering effects of Covid-19 began to take shape, the hotel industry in New York City showed telltale signs of heading in the wrong direction. State and City lawmakers must act fast to reverse the trend, which, if left untouched, shows no signs of improvement. By making any one of the changes we have proposed, the New York State Legislature whether acting alone or in concert with the New York City Council, could address the issue of oversupply and underutilization of hotel space in the city while simultaneously providing for more affordable housing.

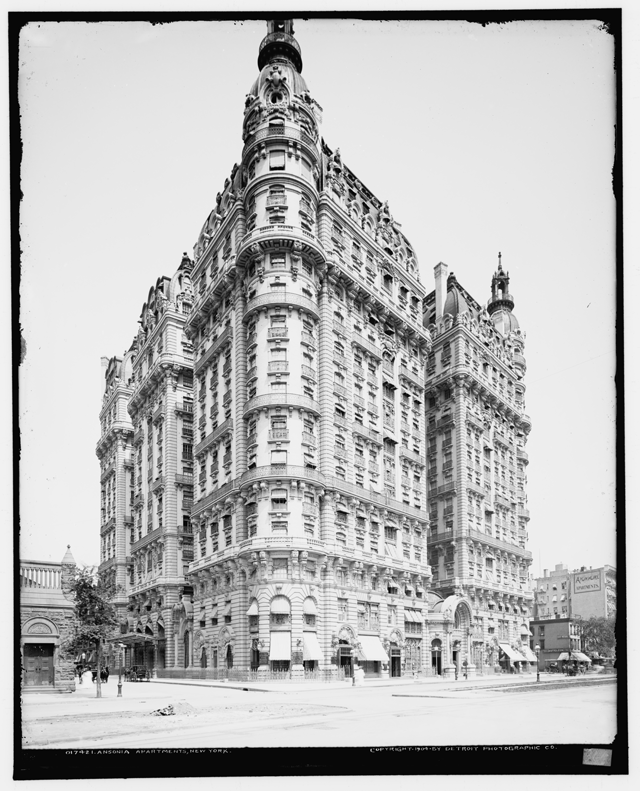

[1] Hotel conversions under J-51 would not be a novel concept. Primarily in the ‘70s and ‘80s, developers were enticed by the program to convert older lofts and hotels, or portions thereof, into Class A residential units, e.g., the Atrium Hotel and Ansonia Hotel in Manhattan, the Hotel Margaret in Brooklyn, and a number of Single Room Occupancy hotels on the Upper West Side, such as the Vancouver Condominium.

[2] As recently stated by the Court of Appeals in Kuzmich v. 50 Murray St. Acquisition LLC, the section was enacted “as part of a broad effort to revitalize lower Manhattan by providing financial incentives to convert commercial office buildings to residential and mixed-use buildings.”

[3] For instance, the following definition could be added to Section 16(a)(xxvii): “Hotel Conversion” shall mean the conversion of a Class B multiple dwelling, including a hotel, to a Class A multiple dwelling.

If you have any questions please call 212-935-1400.

Jay Seiden [email protected]

Jason Hershkowitz [email protected]

Scott Schreiber [email protected]

Zachary Nathanson [email protected]

Frank Baquero [email protected]

Luisa Gutierrez [email protected]